Straddling the provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang, the facility provides a dedicated home for native wildlife

In 2015, Ge Jianping saw a fleeting window that would allow Russian Amur tigers to return to their homeland in China. Monitors had detected 35 such tigers and 70 leopards stalking a tiny patch of forest on the country's border with Russia, which was three times the number the local environment could support.

"It was like the cats were trapped on a lonely island," Ge, former vice-president of Beijing Normal University, told Beijing News in 2016, after the publication of his decadelong study in the northeastern province of Jilin cast the spotlight onto the endangered animals.

On one side of the 100-plus big cats was Russia's protected space, where the predators' fast-growing communities were already testing nature's capacity. The other side was the rolling terrain of mixed needle-leaved and broad-leaved forests in China.

Two centuries ago, Northeast China was home to most of the world's 3,000 Amur tigers — often known in China as the Northeastern tiger — while several hundred lived in Russia. After centuries of excessive hunting and logging, the cats were teetering on the edge of extinction in China. In 1999, a study carried out by China, Russia and the United States concluded that there were only 12 to 16 such tigers in China, compared with about 600 in Russia. "Those cornered tigers and leopards carried the only hope for their kind to return home in large numbers," Ge, 61, said.

However, the big cats' journey home was not easy. Their leafy habitats were fractured by roads, mines and farmland. That prevented the animals from crisscrossing adjacent territories as they migrated, hunted and mated, resulting in a catastrophe for the cats' genetic diversity.

Moreover, herders and herb gatherers were encroaching on natural spaces for financial gain.

In-depth study

In the early 2000s, Ge led a team of BNU researchers into the depths of Jilin's virgin forests. They studied grainy images of the tigers that had been captured by a network of infrared cameras, gave each animal a specific identity and traced their whereabouts.

"Each tiger or leopard has unique markings, just like our fingerprints," said Ge, who holds a doctorate in ecology from Northeast Forestry University in Harbin in Heilongjiang, a province that also provides a habitat for the big cats.

Living in the forest for long periods, the researchers found that going hungry was a daily challenge, while temperatures in Northeast China can easily drop below-30 C in winter. One of Ge's colleagues even ran into a black bear, which he scared away by lighting a firecracker.

The efforts eventually paid off, though. On a baking summer day in 2007, a wild Amur tiger appeared on the screen, and a leopard made its debut three years later.

By 2015, Ge and his team had gathered enough data to conclude in exact numbers that there were 27 Amur tigers and 42 leopards in the area, and possibly in all of China.

Top-level intervention

To clear the way for Northeastern tigers to settle down in China, Ge submitted his findings to the central authorities via a lengthy report, advising that the cats' conservation be handled as a matter of strategic importance.

The number of apex predators such as Amur tigers is widely used as a measure of "ecological healthiness", and their absence would result in excessive populations of deer, boar and many other herbivores, eventually leading to deforestation.

"Without these cats, the ecosystem would not be complete," Ge said.

The report made it all the way to the desk of a senior Chinese leader, who had just started his signature ecological civilization campaign, which prizes the harmonious coexistence of nature and humanity.

He instructed that the tiger's preservation, along with that of other endangered plant and animal species, be included in the country's 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-20), a set of wide-ranging goals to be achieved every five years.

Ge said, "It is safe to say that our efforts led to a sweeping conservation campaign for pandas, Amur tigers and leopards, Asian elephants, and so on and so forth."

The cats' elevated status resulted in the cancellation of a highway under construction and the rerouting of a railway in Jilin so animal migration paths were not disrupted.

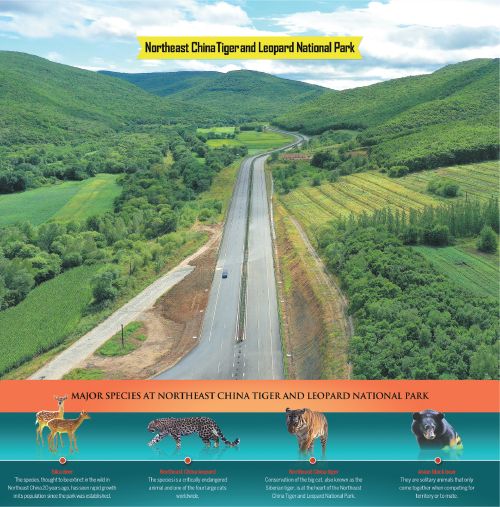

A series of meetings were also convened between top officials and conservation specialists. After lengthy deliberations, they agreed in late 2016 to designate an area spanning 14,065 square kilometers in Jilin and neighboring Heilongjiang as a trial national facility — the Northeast China Tiger and Leopard National Park.

The site, featuring a mix of needle-leaved and broad-leaved plants, also provides a home for black bears, sable and red deer.

An introduction posted on the park's website describes the place as one of the most biodiverse regions on Earth. "The site was chosen to include as much of the tigers' and leopards' major habitats, migration routes and potential destinations," it said, adding that the planners tried to avoid residential areas and they attempted to keep the ecosystem as complete and natural as possible.

Fresh approach

The park's ecological restoration efforts were not new, however. For example, an afforestation project dating back to the 1960s has turned a desert in Saihanba, Hebei province, into a sprawling forest park.

Meanwhile, hundreds of billions of yuan have been spent since 1998 to return cropland to forests and grassland, which has helped to reduce soil erosion along the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River.

However, including a certain species in the country's development plan and creating a national park tailored for its benefit signaled that China's preservation efforts had reached a new level.

At the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China in 2012, environmental preservation entered the blueprint for "socialist construction" as an individual category on a par with the economy, politics, culture and civil society. "The heightened attention on the cats showed that China's knowledge of ecological civilization had achieved a leap forward," Ge said.

A major task during the trial period was to restore the belt-like, continuous "eco-corridors", which allow wildlife to travel unimpeded among the now largely isolated habitats, according to a construction plan on the park's website.

The corridors, which are urgently needed to connect the dots, will help promote genetic exchanges and open a passage for Northeast tigers to settle down in their long-lost home in China, according to a paper published in Natural Protected Areas, an academic journal, in 2021.

Ge said, "To welcome the big cats home, people need to make room for them."